JIEJIE, Mandarin for sister, is directed by Asian-American writer and director Feng-I Fiona Roan. Her film won the prestigious HBO Asian Pacific American Visionary Award in 2018. At its heart, JIEJIE is an Asian American story of first-generation immigration experience from the view of a child.

We caught up with Fiona to discuss what it was like growing up Asian-American in both Asia and the US, and her next big project – AMERICAN GIRL.

1. Both AMERICAN GIRL and its prequel, JIEJIE, were based on your life experiences, coming to terms with your own identity against the backdrop of immigration, repatriation and cross-culture experiences. Was it difficult to share such a personal story on film, one of your cultural identity for a large audience?

I believe as filmmakers we always expose who we are, whether the material is personal or not. However, drawing from autobiographical material based on true events require us to be particularly honest with the role we play in the story. It’s important not to find excuses for your characters, nor to be too judgmental towards their faults.

As directors, our values of the world and what we deem beautiful seep through each and every choice we make in our film. Therefore, I didn’t find sharing a personal story particularly difficult. However, I do feel more responsible towards the way I portray the characters in the film since many are modeled after my family members and friends.

Since AMERICAN GIRL is based on my repatriation experience back in Taiwan in 2003 amidst the SARS epidemic, I have many memories of real events from that period that I can draw from. To maintain an objective distance to the material, I co-write with Bing Li, who story edited JIEJIE. As a professional writer, he keeps me focused on the bigger picture without being overly attached to “what really happened.” We always find ways to dramatize scenes while keeping the situation believable and grounded.

2. In the film you gave both the mother (Lily) and sister (Ann) English names, but not Fen, why is that?

I always try to name my characters closely to the person that it’s modeled after as a reference for how that character would behave. My mom used Rosa as her English name, so I was going for a floral inspired name, and Lily is a common name used by Asians at the time. My sister is named Anny in English, and by removing the “y” and using “Ann” alone, the name could pass off as both a Chinese and English name.

In the case of the protagonist, I was basing the character off of myself, but I couldn’t find a suitable English name that wasn’t too far removed from my Chinese name and wasn’t overly Americanized. Removing the “g” from my Chinese name “Feng” kept the authenticity of the Asian origin while keeping it easy to read. Although my friends now call me by my English name, my family still calls me by my Chinese name. By giving “Fen” a Chinese name, it also helps me stay in the mindset of the teenage girl I used to be.

3. At the heart of the story is the relationship struggle between Fen and her mother. Asian mother / daughter relationships are one of the most complex relationships (thinking JOY LUCK CLUB). How is your relationship like with your mother today?

Ever since I started focusing on autobiographical works, my mom and I actually got closer. Since the writing process inspired us to talk more about her cancer treatment experience at the time, it gave me a chance to hear her side of the story and to sympathize with her as a woman. Removed from my identity as a daughter that had once been traumatized by her treatment process, I was able to see her in a new light as a storyteller.

I’m a big JOY LUCK CLUB fan myself, and I empathize the most with the adult Waverly, especially during the scene with her and her mother at the hair salon. I think what makes a mother-daughter relationship so complex is that daughters almost never want to be “just like our mothers”. In fact, we try very hard to be “everything our mothers are not”, yet find ourselves morphing into them with age. The irony, I believe, is that not even the mothers want their daughters to be just like them. Mothers want their daughters to be “better” than them. “Better”, however, can mean very different things for different generations, and that’s where the complication comes in.

As I was writing “AMERICAN GIRL”, I realized that my sister and I were my mother’s American Dream. My mother wanted us to speak fluent English, and wanted us to have the best chance of succeeding in the world, away from political instability. However, when she fell sick and had to move us back to Taiwan, she felt like she had “failed”. As a teenager then, I wasn’t able to acknowledge her sacrifices and appreciate them.

4. One of the main themes of the movie is the search for belonging and the notion of home. The main character Fen returns to Asia after living in the U.S. as an Asian American for many years, she has changed, home has changed. Where do you call home these days? How do you think the Internet has affected our sense of belonging?

I spent the past year in Taipei because of AMERICAN GIRL, and at the moment Taiwan does feel more and more like home with each passing day. I think home is where one’s family is, and it is where one doesn’t have to explain why one is here. However, it’s often in Taiwan that I realize how “American” I am (i.e. the way I think, my craving for cold-pressed juice, etc). I’ve accepted the fact that I’ll never feel completely at home in one place, and that “home” is an ever-shifting landscape.

With the internet, we can stay “connected” at all times without feeling like a person or place is particularly far away since we get access to them rather easily. In the states, the internet has given minorities (i.e. Asian-Americans) who are often scattered in different areas an opportunity to find each other and speak as a group for their community.

I’m fairly optimistic about the changes that the internet has brought to our world, since it allows us to share and regroup without being limited to borders. Compared to when I was a kid in the 90s, moving back and forth between Taiwan and the States meant that I was completely cut off from the land I left behind. Nowadays, Asians living in Asia and Asian-Americans in North America can easily keep up with the current trend in each others’ countries to get the best of both cultures.

5. JIEJIE was the winner of HBO Asian American Visionary Award in 2018. Just a short year later, the Hollywood premiere of Crazy Rich Asians was monumental for the Asian American community in terms of representation. How was this similar or different in 2018? What are your thoughts on the current state of media diversity and Asian representation in mass media?

Nowadays, Asian-Americans are finding their place in North America by embracing their cultural heritage, and finding value in what we can bring to the American society today, shifting the emphasis of the term Asian-American from the “Asian” side to the “American” side.

The win at HBO was a definitive moment for JIEJIE, since it launched the project to the Asian-American community. To be recognized by a major platform like HBO really was a game changer for all three selected projects, and it made the Asian-American representation in our films more poignant when presented as an ensemble.

Crazy Rich Asians is an American Cinderella story wrapped in an Asian family drama, a long-awaited resurgence of Asian-American stories following great predecessors such as JOY LUCK CLUB and Better Luck Tomorrow. It takes film after film of various genres to truly form a sustainable and marketable movement and change the atmosphere that is backed by the box office. I believe this positive change is in part thanks to streaming platforms and social media, which makes film viewing more immediate and transparent. As our viewing options have widened, we have become more “political” and socially aware when choosing which films and contents we decide to spend our time on.

This.Is.Asia Newsletter Issues

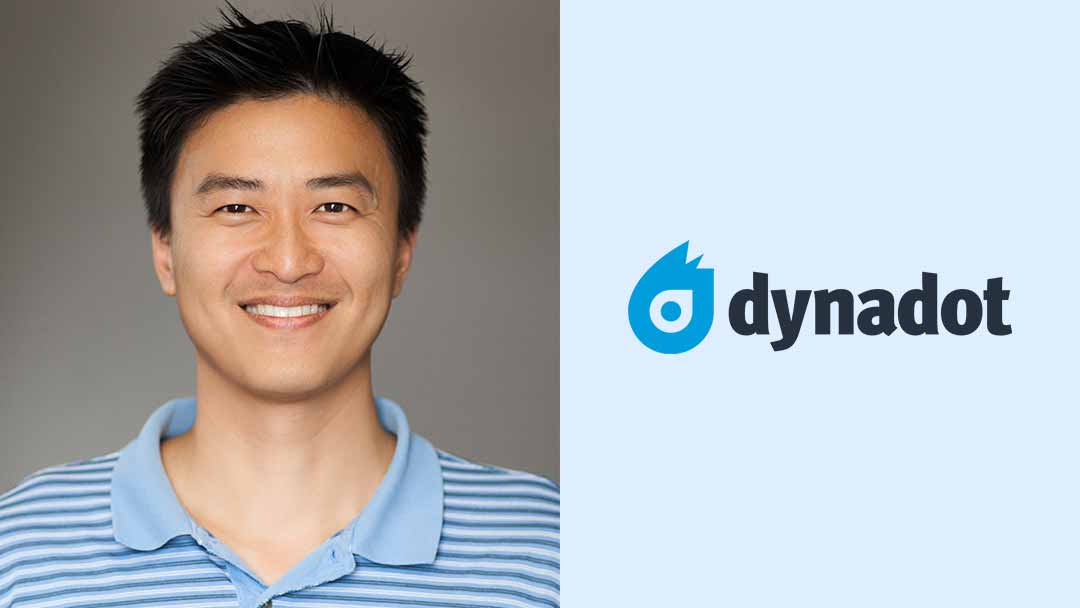

Asian Pacific American Heritage Month – A Conversation with Todd Han, President and CEO of Dynadot.com

Asian Americans contribute significantly to the development of small and medium size businesses in the U.S. In honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month this May, we are dedicating our post to our channel partner Dynadot.com, founded by Asian...

My Favorite Asian American Artists in 2021

Here are some of my favorite Asian American artists and entertainers in films, music, and performing art. I’ve followed their journey for many years. During the pandemic, art became a form of therapy for me.

How I See it – Internet Blackout: Who Are You to Take Away My Rights

Have you experienced an Internet blackout? Such incidence might occur when a city is hit by natural disaster or facing cyberattack. The outage of Internet service experienced by the people of Myanmar recently did not happen because of any such reasons above however, but about politics.

In this episode, Edmon Chung, the CEO of DotAsia Organisation, and Angela Arkandhi, NetMission ambassador — a university student from Indonesia who is passionate about Internet governance and digital policy — are going to explore how the Internet shutdown refrains us from exercising our rights. What are the compromises between tackling the dissemination of false information and ensuring freedom of speech online? Is Internet shutdown not an open-air prison for those who are experiencing it?

Asian American Sustenance

Asian American Food and Identity Food is a vital part of culture. Through food we are joined via a shared experience. It is a connection to our earliest memories, our heritage and some say, an intercultural communicator. Asian American cuisines are a category onto...